“Kwee”

“Ahn-doh woo-kwee,” I had commented as I searched among a sea of red synthetic gowns. It was 2010 and in typical Hakka family formation[1], my parents, brother, cousins, aunts and grandparents and I were attending my sister’s graduation from university. My father paused briefly before responding, “Heh...”

There were a number of things that were wrong with that moment. For one, what I had said had translated into, “There are a lot of Indians.” As a teenager, I problematically didn’t see the issue with making assumptions about a person’s identity based on their appearances. And though I had made the comment to somehow ground familiarity in the setting (as a teenager, I had yet to understand the nuance in being Hakka from India, and that having history in India did not privilege me membership into shared experiences), it didn’t lessen the fact that I was showing my own internalized colorism and racism. While we can aspire to recognizing that empathy should be our pre-choice and not a reflection, my awareness of race, ethnicity and language changed drastically after experiencing those labeling frustrations from people who similarly tried to tell me who I was before I could tell them.

The real reason for why my father paused was probably the same reason my cousin immediately snapped her head in my direction and stared at me. That word. Kwee. In Mandarin, it would be gui, or 鬼. The term is meant to be a derogatory one, and it can mean ‘devil’ or ‘ghost.’ And ‘woo-kwee’ translates into ‘dark-colored ghost.’ While this doesn’t sound so malignant when translated into English, the word is a curse and deeply ingrained in a sense of superiority and colorism.

I did not know what it meant to call someone a kwee at the time. Hakka people often joke that we the only people we acknowledge in this world are Chinese. According to our language, it’s true. We call ourselves ‘tong-ngin,’ or tangren (唐人) in Mandarin. Everyone else is a kwee. If you’re White? Pak-kwee. If you’re Black? Heh-kwee. Foreigners? Fan-kwee[2]. Those annoying customers at your store and/or restaurant? Hak-kwee. The word is so commonly used, that some people don’t really acknowledge the nuanced difference in calling someone a kwee and calling them a ngin.

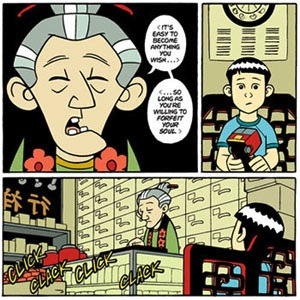

Whenever I bring up the problem with saying kwee to other Hakkas, some push back and ask, “But what’s so wrong about being called a ‘kwee’ anyway? It just means calling them a ‘ghost.’” When we were kids, my siblings and I often heard these words, but we never thought too much about what kwee meant. It was simply part of that foreign language that our parents used whenever they wanted to talk badly about other people behind their backs. I had heard the word kwee thrown around so much and had never really reflected upon what it meant.

Ghosts in American culture are often times simply scary characters in films. Some people believe in them, some don’t. For those who believe in them, ghosts are lost souls of people who left the world unsettled. These people could have been troubled, angry, frustrated or sad. They became lost souls not because of their own fault, but because of the people around them. In movies and TV shows, they are portrayed in a more empowered light, taking their revenge on people, invisible only to appear invincible.

In Chinese culture though, ghosts are interpreted a bit differently. In Chinese culture, the individual is inextricably linked to others; parents, friends, children, siblings. Ghosts, however, don’t have these people. They are wretched because they committed grave sins, failed to fulfill their social duties to their family and community, and did something so dire that even their own family wouldn’t honor them in the Afterlife. In Chinese culture and language, ghosts don’t have friends, family, community or culture. They are incomplete and the living go on without them, not wanting to remember them. Without all of these things, a ghost really has no soul, and there really can’t be anything worse than to be a ‘kwee.’

Stuck in Time: Understanding my Father

Ahpak, Ahyee, Koo-koo, Ahkiu, Kiu-me, Pak-me, Ah-ko and Ah-ji. These were the kinship terms we learned as Hakka children.

We were celebrating Chinese New Year at my grandparents’ house. While helping my father unload something from our car, my cousin called out, “Hey, Michael…” My father squared his shoulders and pointed his index finger at my cousin. “Look, it’s Uncle Michael. Don’t just call me by my first name. That’s what Americans do, but you ought to have some respect for me. Do you understand?” My cousin stood silent while the rest of us looked away, not necessarily disagreeing with what my father had said, but how he had said it.

There are dozens of memories like this, where I remember the exact expression on my father’s face. It was not mere anger, but it was also defiance, determination and fear. Immigrants who hold on to their traditions are often labeled as anti-American, too uneducated to fit into American society. But the real problem is perhaps that Americans are anti-multiculturalism. As I’ve traveled around the world, I’m disturbed by how many people truly believe that the United States is a good example of an immigrant nation. Yes, we are a melting pot, in a sense. A melting pot into which all ingredients must blend into one another, no longer maintaining their own individual flavor.

As immigrants’ children, my siblings and I look back. Unfortunately, we also looked down. We looked down when my mother ignored us every time we corrected her for saying “I’m not interesting” when she really meant to say “I’m not interested.” We looked away when my father demanded our friends remove their shoes when they walked in our house. We walked away when our extended family filled the ICU with their bodies and reused containers of homemade food to visit my mother after her heart attack. There were a lot of things we would never understand about our parents—maybe because we lacked empathy. Maybe because we didn’t know their fear.

Fear of what? At one time, I would have answered that my parents were afraid of losing their culture. But that response is a cliché expected from most immigrants. Their fear was so much more political, so much more aware of the social processes and dynamics going on around them. My parents weren’t fighting for the survival of the entire Hakka culture. They were fighting for their autonomy to decide what it meant to be American on their own terms, in their own house, in their own family, in their own skin.

My parents didn’t fear losing their culture. I think most immigrants in the US have the wisdom to understand that change is inevitable. But what my parents, like so many other immigrants, feared was being looked down upon for being so visibly in the process of change and growth. Their circle of friends and family was already small, and they feared it would get even smaller and smaller, shrinking until no one would be left, except themselves. But like so many other immigrants, sometimes the harder they fought, the more they were condemned.

Insult or Endearment?

Pan-hsien. Pan-now-sit. Fan soo. Fan-kwee. Fan-see-oh. See-say-kwee-eh. Woo-kwee. These were the type of words I commonly heard from other Hakkas I knew. As a child who couldn’t understand or speak Hakka fluently, I didn’t realize at first that these weren’t the nicest things to say. Similarly, I don’t think my parents thought much about how these words translated into English until we asked them later on.

Need some context? A pan-hsien is a half-blood; someone who is of mixed heritage. A pan-now-sit is a half-brain; someone whose head is mixed with Chinese and non-Chinese thought. A fan soo[1] is a stupid idiot. A fan-kwee is a foreign ghost. Fan-see-oh! is ‘annoyed to death.’ See-say-kwee-eh means ‘little ghosts’ and is what some people call their own children, sort of like calling one’s children ‘my brats.’ And woo-kwee was what we called dark-skinned people. For Hakkas from India, that’s how they refer to Indians. For Hakkas in Mauritius, that seems to be how some refer to Creoles.

My parents outgrew this vocabulary, but it’s still a part of my community. Not everyone saw the value in this though. It came as a shock to me when I realized how much other Hakka parents continued to speak the language without thinking twice about the vocabulary they were using. In particular, it bothered me that some people still referred to girls as “little slaves” or even “cunts.” In one case in Europe, a friend had joked that his mother more or less called me a cunt. I was livid. He replied,

“Relax, it’s just a term of endearment.”

I couldn’t see it as a term of endearment. In the US, people have studied the reclamation of words like ‘bitch’ and ‘nigga.’ The name ‘Hakka’ itself is the reclamation of a Cantonese insult. Not all people of mixed Hakka heritage see the term ‘pan-nao-sit’ as inherently hateful or mean-spirited. Yet no matter how hard I tried to keep an open mind about my social position, education and language differences in relation to my friend’s mother, I couldn’t accept or brush it off.

I didn’t blame his mother. Rather, I blamed him for telling me to see it as a term of endearment. I was angry that someone told me to calm down and frustrated that there wasn’t a chance to discuss why I was opposed to the term. An entire section of not only the Hakka language, but almost every language in the world, is dedicated to degrading women, their bodies and their value. Most of all, I was frustrated that I didn’t have the full language capacity to stand up for myself. No, I blamed him for being too afraid to speak up when he had the power to do so.

So much of that vocabulary revealed how little the language has changed, mainly because so many native Hakka speakers have not critically confronted or challenged the language. That’s not to say that there aren’t Hakkas who never challenge or advance their language. Some would reduce youth’s inability to speak their mother tongue to generation gaps, disinterest in their roots, or personal weakness. The problem though? In Anthro jargon, I’d phrase it as “lacking cultural capital.” In short, those who would like to confront casually calling people soulless ghosts or female genitalia don’t feel that they have the authority to do so. Part of it has to do with not speaking the language fluently. A larger part of it has to do with knowing that it’s an uphill battle against a society that struggles, and often fails, to look inward.

“The problem with Hakkas is that they don’t want other people to know the problems they have within their own society.”

Nothing but Nostalgia

When I first came to Mauritius, the Hakka people I met proudly told me of how their folks from Moi-yen would praise how they spoke the language whenever they went to visit or reconnect with their roots in mainland China. Mauritian Hakkas could still speak the language just as it was spoken in Moi-yen. This is the same thing that I hear Hakkas from India say about themselves.

Pure Hakka. I consider the language, the way it contradicts some of the very concepts and tenets to which Hakkas hold claim, yet fall short internally. Things like feminism or tolerance or adaptability. If that’s what it means to be “pure Hakka,” is that really a good thing?

In nearly every country I’ve visited, I’ve met people who have asked me what is the future of the Hakka people. In some online Facebook groups and forums, I’ve seen an array of fatalist responses and some extreme calls to action to return to China, even. Most relevant my research, I’ve met some extreme cases of people who insist that their sons marry Hakka women for the sake of ensuring “family success” because they believe Hakka women know how to bear the burdens of a difficult life.

Over the year, I’ve come closer and closer yet simultaneously farther and farther from understanding what it means to be Hakka in a rapidly globalizing world. If there was one way to sum it up though, I’d say that Hakka culture is by now a collection of glocalized cultures. Others interpret change as threat though as it becomes harder and harder to recognize our counterparts across borders and oceans.

I often find myself falling into the trap of looking for “authentic” Hakka culture, though I ought to know better. I find myself looking for people who still make fong mee mien that melts on my tongue, or Hakka grannies puttering around their homes because they can’t sit still for more than 5 minutes. I look for people who speak the same Moi-yen dialect as my family, and I look for people who can sing the same folk songs as my grandparents. It seems that I find myself looking for nostalgia. I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that I grew fond of Mauritius because it has been one of the few places that reminds me of where my family came from.

But to reduce our culture to these nostalgic markers would be incredibly unjust and selfish. Nostalgia can motivate people to look inward, but seldom critically when we get caught up clinging to the familiar. Our culture, if it is to survive, needs to make space for change. That starts with ensuring that young people feel that they have the authority to not only participate in it, but lead in their society.

Leading goes beyond asking young people to execute orders, recruit volunteers or figure out tech-related tasks. It entails taking young people seriously enough so that they may confront aspects of their culture when they see that it no longer reflects a world in which they feel proud, affirmed and accountable. Perhaps elders fear that change brings an end to the world they remember. Far from it though–for a culture unchanged and untouched is not much different from a specter of something that once existed.

[1] Hakka families are traditionally huge. It’s common to run into grandparents or even parents who had between 10 and 12 siblings. As a result, we tend to have a ton of cousins, who are our playmates and the primary Chinese “community” we know. Hakkas have often been described by other Chinese as being “clannish” for keeping to themselves. It’s a bit true; we tend to travel in large packs and prioritize our own clan. Make way for us and all the snacks we’re bringing with us.

[2] Ironically, this is what Hakkas call the locals of the country they just immigrated to.

[3] ‘Fan soo’ is also a type of yam commonly found in Moi-yan. They are so common that it became an insult to call someone a fan soo as a way of telling someone that they are so plain and ordinary. English equivalent: “You are basic.” Oh, they’re also purple in color.