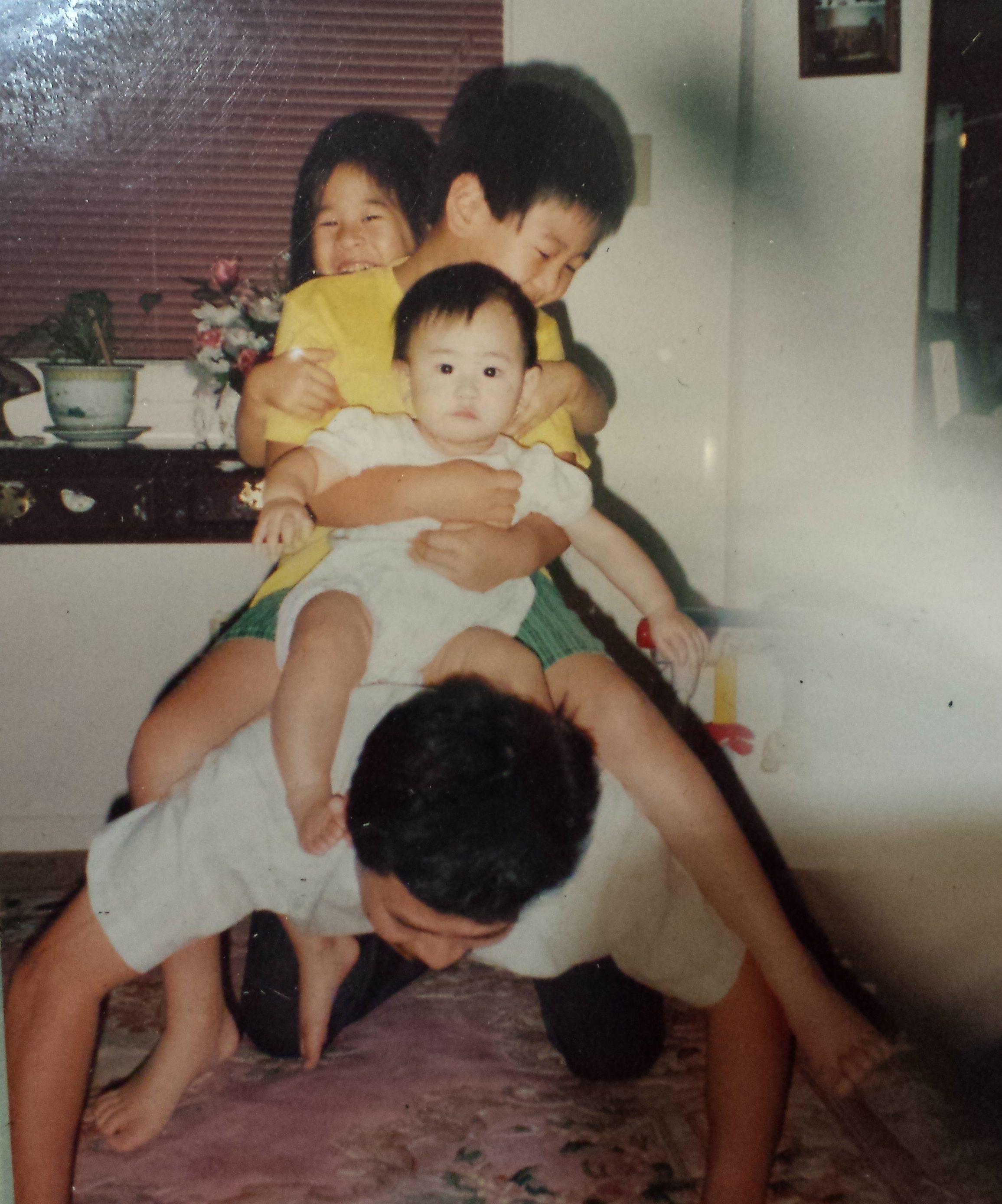

About my parents…

It was sometime in May that I spent the day over at a Mauritian couple’s home. Mrs. Yip had excitedly offered to teach me how to make ngiouk yan–a dish that I never liked that much before coming to Mauritius.

Ngiouk yan is a traditional Hakka dish, usually made of minced meat and shredded white turnips, held together by cornstarch and steamed to form opaque bite-sized lumps. But in Mauritius, families tend to cook them instead with shredded chou chou–a sweeter, delicious substitute to turnips.

As Mrs. Yip taught me how to roll the mixture into small balls with the palms of my hands, she asked me about my family. Did they speak Hakka at home? Not really, mostly English. Did we eat ngiouk yan often at home? Nope, my mom didn’t have a lot of time to spend on cooking each day. Did my mom cook Hakka food at home? Sometimes, but we like Indian and Pakistani food, too. Did my mother work, or was she a homemaker? Yes, Mom worked. So who looked after you when you were growing up?

A lot of people took care of me. And Mom was superwoman; our customers would always joke that she was the real boss, teasing my father for never being around to watch over his own restaurant. Looking back, it did create tension in our family. Undoubtedly, my mom worked hard. She worked 10 hours a day, nearly 7 days a week, with only half of a day off on Saturday when we closed for lunch. That didn’t include all of the housework and family obligation she had to take care of.

When I was very young and didn’t understand, I used to feel angry that Mom was working so hard every day in the restaurant. I heard people say about my dad, “How can he let his wife work so hard?”

But as Mrs. Yip asked me more about my family, I told her more and more about my dad and remembered all the things he did to take care of me.

The Little Things

In first grade, I owned a pair of maroon corduroy pants. It was the first time I had a pair of pants that weren’t leggings. I wore them until the knees had holes in them, and yet, I didn’t want to give up wearing them. My classmates made fun of me for wearing clothes with holes in them, one girl even telling me I must have been really poor. I told my dad about it–I was afraid that if I told Mom, she’d make me throw them away–or even worse, cut them up into rags to wipe the table; and then I wouldn’t have any pants to wear to school anymore.

The next morning, I found my corduroy pants. But instead of finding two holes at the knees, there were two heart-shaped leather patches. The leather was neatly cut and smoothed at the edges, and the stitches were so even and straight. I turned to my dad and told him excitedly that Mom must have fixed the holes for me. He smiled. “No, I did.”

Years later, in middle school, my friends’ mothers always packed their children’s lunch boxes. My friends’ moms typically packed fruit, a sandwich, yogurt, some juice. When I unpacked mine, my classmates would always watch eagerly. Some days, I had pork fried rice kept hot in a thermos, other days I had a fresh salad with tandoori salmon filet. My friends asked me incredulously, “Did your mom get up and make that this morning?” I smiled. “No, my dad did.”

When I went away to study when I was 16, my dad would sometimes drive a total of 8 hours in one day, even if it meant only seeing me for a mere 3 hours. Each time, he would bring all the things he thought I needed. Herbal soups, jackets and sweaters, fresh milk, containers of fresh homemade dumplings, chocolates that my mom had packed, my favorite brand of instant noodles. One weekend, my dad drove to take me home since we had an extended weekend–a total of three whole days. I didn’t realize it until my friend commented as I was preparing to leave, “Your dad must really love you if you he is driving a total of 16 hours just to take you home this weekend.”

When I went to Davidson, my dad looked forward to any chance to visit campus. Fortunately, it was only an hour away from home this time. He drank coffee and enjoyed bluegrass music with me in Summit, went to evening lectures that ranged from fascinating to snore-inducing, entertained simultaneously ridiculous and thoughtful discussions with my friends, and brought trays of fresh food from Chen’s. My friends, classmates and professors, whether they liked it or not, became accustomed to “Yeeva’s dad.”

Not so little

These were the “little things” that made a world of difference to me.

I have sometimes questioned if these acts seemed so much bigger, more meaningful in my mind simply because it was my dad who did them instead of my mom. If it had been my mom, would I have been less grateful because these acts of care are so often expected of mothers instead of fathers?

I think back though to how much my mother’s work was valued for so visibly supporting our family when it came to finances. And how that also came with the occasional emasculation of my father when family or friends talked about him for not being at the restaurant as much. It’s true, my mother was exhausted at the restaurant. Though it didn’t negate the ease that comes with male privilege, my dad wasn’t exactly taking it easy either. He was experiencing the same work load and ridicule that women often receive for their role in raising a family.

I can’t say that my father made the conscious decision to subvert gender expectations, but regardless, he certainly did. Perhaps his unconsciousness about those decisions though was what made it all the more beautiful–he wasn’t trying to be bold or political; he just wanted to do the things he hoped would make his family happy and healthy, out of love.

There are a number of ways that I want to direct this post toward third wave feminism, gender equality paradoxes, glass ceilings and gender role swapping. But in honor of Father’s Day, I’m going to instead end with a part of the email I wrote to my dad:

HAPPY FATHER‘S DAY, DADDY!!!!!!

I consider myself a very blessed daughter. Thank you for always encouraging me to dream big.

It made all the difference in my life because even though I didn’t have a parent who could always tell me the answers or guide me in school, I knew I had parents who did everything and anything in their capability to show that they supported me and wanted me to succeed and wanted me to feel valued. Too many people say “I love you” so easily, but I have parents who always showed it.

Love,

Yeeva